CindyGL Tutorial - Live Coding

For the very beginning, we propose that you start learning some CindyScript via live-coding. This tutorial does not require any prerequisites. However, some background in programming is always helpful.

Live coding means that you can type some CindyScript in the code-window on the right. If the code is valid, the applet will instantaneously process the input. You can also click on the big yellow code snippets within this tutorial to load the code to the live coding applet.

If you are already familiar with CindyScript, you can directly proceed to the section "The colorplot-command" to start with learning about CindyGL.

Drawing points and lines

We will start out with the basic drawing command draw

draw( (0,0) )will evoke the display of a green point in the center of the applet. (0,0) is a 2-component vector representing the origin of the applet. In CindyScript, one can equivalently write [0,0] instead. You can try to draw the point at another position. Here, the applet here covers all coordinates between -2 and +2.

In CindyScript, multiple commands can be concatenated with ;.

You can draw an additional point on another position if you extend to code to

draw( (0,0) );

draw( (1,-0.5) );The ; ending the first line seperates the two draw-commands.

Actually, the ; in ending the second line is not demanded, because there is no further command. However, it is a good style to always finish commands with ;, since then one can easily append more commands without causing an error.

Moreover, you can connect the two points by a segment by calling the draw command with the two coordinates as arguments:

draw( (0,0) );

draw( (1,-0.5) );

draw( (0,0), (1,-0.5) ); //comment: Draw a segment!As you can see, comments in CindyScript are triggered with the //, CindyJS will ignore the rest of the line.

Let us add some exciting movement to a visualization!

For example, if you want to see a point moving, you have to give time dependent coordinates as argument for draw, for example you can use the seconds() function. seconds() returns the absolute time as a real number (Actually seconds() returns the time that passed since the last time the resetclock() command was executed. In this live coding applet resetclock() is run once when the page is loaded). Let us use trigonometric functions to move a single point on a circular orbit:

draw( [cos(seconds()), sin(seconds())] );When running this code, you should see a single point spinning around counterclockwise (taking exactly 2*pi seconds for a whole rotation). Technically, the program is executed for every rendered frame. Later, these program snippets will be part of the draw-script.

Could you build a simple animated applet that shows a clock with several clock-hands?

Colors

Colors are essential in visualization. In CindyScript, a 3-component vector with entries varying from 0 to 1 represents a color. The entries stand for the parts of the primary colors red, green and blue for an additive color mixing.

If you want to modify the color and size of the drawn point, you can use modifiers in your program:

draw((0,0), color->(1, 0, 0), size->10);It draws a red point. (1, 0, 0) means full red and no green or blue.

Instead of entering vectors for colors, you can access colors through the functions gray(value), red(value), green(value), blue(value), which all take a value between 0 and 1 and outputs a corresponding color-vector. 0 stands for black and 1 stands for the bright color.

Let's paint a light-blue point with:

draw((0,0), color->gray(0.5) + blue(1), size->10);The function hue(value) will take a color from color wheel with a given hue. hue of every integer equals to red. Any fractional value in between will describe a bright, fully-saturated color along the color wheel. For instance, if $k$ is an integer, then hue(k) is red, hue(k+1/6) is yellow, hue(k+1/3) is green, hue(k+1/2) is cyan, hue(k+2/3) is blue.

What hue does can be seen best from the following command:

draw((0,0), color->hue(seconds()/4), size->10);Basic control structures in CindyScript

In CindyScript every control structure is a function. A useful control structure is the repeat loop. repeat(‹number›,‹var›,‹expr›) takes three arguments: the first is the number of repetitions. The second is the name of the running variable (which will run from 1 to ‹number›) and the third argument is the code that is executed for each repetition (the second argument can also be skipped if the running variable is not needed). For instance, a color wheel can be drawn as follows:

repeat(100, i, //repeat 100 times

draw( (cos(i*2*pi/100), sin(i*2*pi/100)), color->hue(i/100) )

);In this example, the duplicate term i*2*pi/100 might have looked a bit cumbersome to you. It could be computed only once and saved as a variable, which is to be accessed whenever it is needed. Variables can be assigned with =. Usually, the domain of a variable is global in CindyScript (using regional(varname) a variable can be made regional).

For example, the following code produces a sunflower and uses some auxiliary variables to increase the readability.

repeat(500, i,

w = i*137.508°; //° is equivalent to *pi/180

p = (cos(w),sin(w))*sqrt(i)/15;

draw(p, size->sqrt(i)*.3, color->hue(i/34));

);Another important control-structure is the if-operator. The conditional operator if takes a minimum of two and maximal three arguments. The first argument is a boolean expression. If it evaluates to true, then the second argument is evaluated and returned. If the boolean expression is false and a third argument exists, then the third argument is evaluated and returned.

In the following example, the drawtext(‹vec›,‹string›) operator will draw text to a given position. The string will depend on the position of the mouse:

drawcircle((0,0),1); //draws a circle with radius 1 and center (0,0)

drawtext((-1,0), "The mouse is " +

if(|mouse()|<1, // | | denotes the euclidean length of a vector

"inside", "outside") + " the circle." );The colorplot-command

So far we have seen only draw commands that were more like pencil operations: For each operation, we had to specify a location. Often one wants to paint something everywhere. The colorplot-command assigns a color to each pixel given a function.

Let us first start with an simple example:

colorplot(hue(seconds()/4));Here every pixel gets a single color. It is important that the return value of the code that is given to colorplot is a color, as it has been described in the Section Colors.

To make the color dependent on the position the pixel, you can access the pixel-coordinate via the variable #. # is a 2-component vector. Its first entry can be accessed with #_1 or #.x, its second with #_2 or #.y.

An example that accesses the variables is the following:

colorplot(

(1/2+#.x/4, 1/2+#.y/4, (sin(seconds())+1)/2)

);With this, the red/green-component depends on the x/y-value of the pixel coordinate and the blue component varies with the time. All the three values have been rescaled such that they lie between $0$ and $1$.

Now, let us try to visualize the color wheel, we have seen above, but without the draw-function. For drawing a color wheel, a colorplot is probably more appropriate: Instead of thinking of how to sample 360° and deciding where to draw points, we want to assign a color to every pixel visible of an annulus (ring).

So what do we need? First, we want to draw something within an annulus. Given a pixel coordinate #, we can check whether it lies within an annulus for example with 1<|#| & |#|<1.1. By using some branching with if we can compute different colors when we are inside our outside the annulus.

If we are inside the annulus, we want, given #, calculate its angle to the origin and color the pixel according to this angle. The angle can be obtained by using arctan2(#). arctan2 is a convenience function, that is also available in various other computer languages, and returns the angle of a vector; Using something like arctan(#.y/#.x) instead would omit an important information on # because the sign sometimes cancels in the division. For example, $\frac{-1}{-1}=\frac{1}{1}$ and therefore the vectors (1,1) and (-1,-1) would yield the same value for arctan(#.y/#.x).

To feed the computed angle, which lies between $0$ and $2\cdot \pi$, to the hue-function, we have to rescale it to fit the whole color-domain by diving it by 2*pi.

Altogether, we obtain the following code:

colorplot(

if(1<|#| & |#|<1.1,

hue(arctan2(#)/(2*pi)),

grey(0.4) //use grey outside the annulus

)

);Interference of two waves

Next, let us build a visualization of the interference of two waves. We assume that there are two circular sinusoidal waves with the point sources p0 and p1.

We assume for the visualization that the equation for the amplitude of a sinusoidal wave with point source $p$ at position $x$ and time $t$ to be $\sin(20 \cdot|x-p|-t)$. $20$ is only a scaling parameter that the visualization looks nice on the screen. Let us define a helper-function with W(x, t, p) := sin(20*|x-p|-t);. The operator := always indicates the definition of a new function. The return value of a function that is defined by a sequence of commands separated by ; is the value of the last expression.

To test this function, let us visualize a single wave with source (0,0):

W(x, t, p) := sin(20*|x-p|-t); //helper function

colorplot(

gray(1/2+1/2*W(#, seconds(), (0,0)))

);We want two waves to superpose. To compute the superposition of two waves with different sources, the amplitude-values of two such W functions are added to a variable u. Based on this number, which lies between -2 and +2, a color is assigned for each pixel coordinate #:

W(x, t, p) := sin(20*|x-p|-t); //helper function

p0 = (-1,0);

p1 = (1,-1);

colorplot(

u = W(#, seconds(), p0) + W(#, seconds(), p1);

gray(1/2+u/4) //the last line is the return value!

);When running this, observe the interference patterns!

In a general setting, CindyJS can also interact with a geometric construction, and it would be a good choice to choose draggable points for p0 and p1. In this live-coding applet, no geometry is possible. However, you can try to replace the coordinates of these points with mouse() to obtain more interactivity.

A strength of CindyJS it that it will run these codes on the GPU, which makes it very fast and suitable for real-time visualizations.

Complex phase portraits.

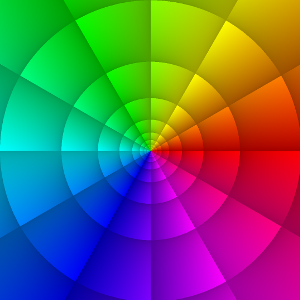

A way to visualize complex functions $f:\mathbb{C}\to\mathbb{C}$ is the use of phase-portraits. A complex number can be assigned a color according to its phase/argument. Positive numbers are colored red; negative numbers are colored in cyan and numbers with a non-zero imaginary part are colored as in the following picture (which also can be considered as a phase portrait for the function $f(z)=z$):

In his book Visual Complex Functions Elias Wegert employs phase portraits as an access to the theory of complex functions. For instance, roots and poles of a complex function $f:\mathbb{C}\to\mathbb{C}$ can be easily spotted at the points where all colors meet.

Generating phase portraits can be easily done on the GPU with colorplot: First let us define a complex function $f:\mathbb{C}\to\mathbb{C}$. A interesting function could be $f(z)=z^5-1$, which should have the five roots $\exp({k \tfrac{2 \pi i}{5}})$ for $k\in\{0,1,2,3,4\}$. We define $f$ in CindySript with f(z):=z^5-1.

CindyJS supports complex numbers and all its operations without additional implementations. One could evaluate f(i) and get $f(i)=i^5-1=i-1$:

f(z):=z^5-1;

drawtext((0,0), f(i));Now we want to build a colorplot that interprets each pixel coordinate # as a complex number z, evaluates f(z) and colorizes the complex number f(z) according to the image above.

In order to interpret # has complex numer z one can either write z=#.x + i*#.y or use the equivalent function z=complex(#), which converts 2-component vectors of real numbers to a single complex number. Then we evaluate $f(z)$ and save it to the variable fz with fz=f(z). Now, in oder to colorize it, we will again use the arctan2 function, which can also applied to complex numbers, to obtain the angle/phase of fz and plug the rescaled angle in the hue function:

f(z) := z^5-1; //a complex function

colorplot(

z = complex(#);

fz = f(z);

hue(arctan2(fz)/(2*pi))

);

The colors in the result do look not exactly as the colors above. The visualization can be enhanced if lines of the same phase and modulus are highlighted. To generate the image above, The following more complicated helper function colorize can be used that gives colors to complex numbers:

f(z) := z; //a complex function

colorize(z) := (

n = 12; //highlight 12 different phases

z = log(z)/(2*pi);

zfract = n*z - floor(n*z); //n*z in C mod Z[i]

factor = (.6+.4*re(sqrt(im(zfract)*re(zfract))));

hue(im(z))*factor; //darken hue wrt factor

);

colorplot( colorize(f(complex(#))) );The trick in designing colorize is to notice that the imaginary part of the logarithm of a complex number corresponds to the argument of the complex number, while the real part of the logarithm equals to the logarithm of the modulus of the complex number. By adding a grid over the values obtained by taking the logarithm, a grid that has iso-lines on phases and moduli is obtained. You might have wondered why there is a re in re(sqrt(...)) in the code above? The problem is that CindyGL needs to be able to prove the types of all occurring variables and a colorplot should return a real color vector. If one takes the square-root of a real number, then the result, in general, is complex. To guarantee CindyGL that factorwill always be real, we take the real part of the square-root.

Now is maybe a nice time to play around with other complex functions. For example, what happens for f(z):=(z+1)/(z-1), f(z):=sin(z), f(z):=z^(complex(mouse()))...?

Plotting the Mandelbrot set

An application that is almost tailored to the colorplot-command is the visualization of the Mandelbrot set. The Mandelbrot set contains all those points $c\in\mathbb{C}$ such that the iteration $z_{n+1} = z_n^2+c$ starting with $z_0 = 0$ is bounded.

A simple algorithm for plotting the Mandelbrot set is known as the "escape time" algorithm. It is based on the observation that whenever there is a term in the sequence having an absolute value larger than 2, the sequence $z_n$ can be proven to be unbounded. So we will compute the sequence $z_n$ for every pixel having the complex coordinate $c$ for a while and check whether it will leave the circle of radius 2. The number n of steps that the orbit remains within the circle of radius 2 is a possible ingredient for a visualization.

N = 30; // maximal number of iterations

colorplot(

c = complex(#)-0.75; //center -0.75+0*i

z = 0;

n = 0;

repeat(N, k,

if(|z| <= 2, // if we are inside circle,

z=z*z+c; // then iterate and

n = k; // increase n

);

);

grey(n/N); // the last line is the return-value!

);The earlier we leave the circle of radius two, the smaller is n and the darker is grey(n/N)

Can you create a 15-second movie that zooms to the point (-0.7436439 + 0.1318259*i) of the applet? You might use mod(seconds(),15) to obtain the needed "time-coordinate".

For a given $c\in\mathbb{C}$ (for instance, c=-0.4+0.6*i or the mouse-coordinate), can you color-plot the filled Julia and Fatou set of the function $z^2+c$? That is the set of all points $z\in \mathbb{C}$ such that the orbit $z_{n+1} = z_n^2+c$ starting with $z_0 = z$ is bounded.

Wrapping Up

CindyGL basically supports a colorplot command that colorizes each pixel within an applet. colorplot takes an CindyScript-program that and will be transcompiled to the GPU. The pixel coordinate within colorplot can be accessed through #.

You can continue our tutorial by learning how to build real applets here.